Lenses: The Eternal Question

The moment you get sucked into the DSLR racket – or even as you consider it – you start the never-ending journey of asking yourself what lenses you need. There’s really no way out of this; even if you bought every lens available for your camera (recommendation: go with something like the Sony NEX-5 that only has a handful of lenses!), you’d still probably check nikonrumors.com to see if anything new came along that you now need. Almost exactly three years ago, I bought my first DSLR (Nikon D60), with a “do all” 18-200mm zoom lens that I never intended to take off the camera. 10 lenses later, I can’t say that this was a particularly accurate prediction.

Still, about half of photography forum chatter seems to be either “what lens should I buy” or “what lenses should I take on a trip to… my backyard”. Amazingly, this question comes up a lot offline too; in one day, I wound up E-mailing my brother about lenses for a wedding his friend asked him to shoot (major pressure for a non-photographer!), and my friend Herman who is getting further along in pondering his switch to Nikon. A little planning here is important, so you don’t wind up like Greg from my work, with a 16-85, 24-120, and 28-75 in a collection of just five or so lenses total (due to the significant overlap). Or like me, with 10 lenses instead of a planned 1.

Lens selection is a 7-way trade-off between focal length coverage, maximum aperture, build quality, price, size, weight, and features (AF, VR, macro, etc). Some of those (e.g. size & weight) are linked, others less so. If the best lens wasn’t highly situational, there wouldn’t be so many of them. This creates the usual photographer vs. non-photographer dilemma; what’s very good advice for an aspiring photographer can be very different from the right choices for a non-photographer.

With that said, how and what should a non-photographer choose?

Part 1: Learn From Yourself

Especially if you’re just starting out, there’s two things hugely in your favor when it comes to choosing lenses:

- A highly competent kit lens is just $150-200 over buying the camera body only and getting alternative lenses separately. On Nikon, you’d get a 18-105mm zoom with VR, which will already far outperform any compact you may have owned. This will be sufficient to learn what you really need, and gives you a good initial range.

- Lenses actually hold their value quite nicely, and as a result, if you ever decide that you want to go a different route, you can often recover close to the full value if your kit lens if you didn’t get the very entry level 18-55mm that wouldn’t be an upgrade for anyone.

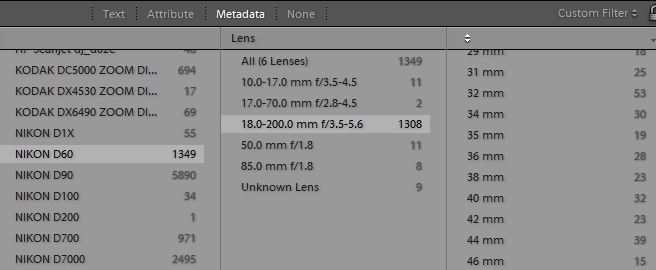

The nice thing about digital photography is that every choice you ever made is recorded somewhere, just waiting to be analyzed – what lens you used, at what focal length, aperture, shutter speed, whether you used flash, ISO, etc. If you use Lightroom, you can filter by meta-information in the library view to get some insight – like what focal lengths you use most often with a given camera & lens:

Now, Lightroom isn’t free (especially relative to a $150 kit lens!), and even if you have it, the above presentation isn’t great. Fortunately, there’s free tools that can extract EXIF information from your JPG files (or directly from raw files). Several are available, but one I’ve used is ExifPro, available at http://www.exifpro.com/; it’s free though if you use it regularly you can buy a license.

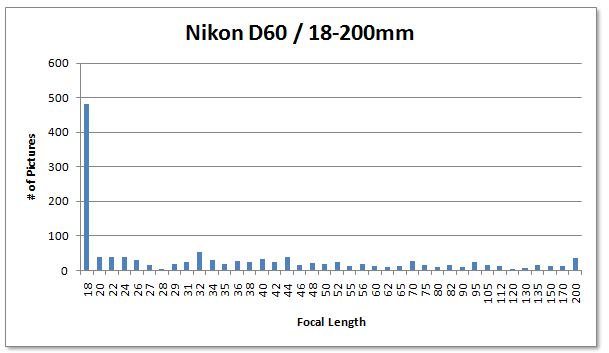

Using ExifPro, I just select all my photos, add columns for camera and lens type, export the EXIF data to a text file, and then use something like Excel to graph your actual usage. In a few minutes, you can have a simple chart like this:

This is my actual usage of my first DSLR, the D60, with “only lens I’ll ever need” – the 18-200 VR. Looking at the graph above, what do you think I bought first – an ultra-wide lens (covering less than 18mm), or a longer telephoto (more than 200mm)? Not hard to guess the answer to that question; I was stunned at how often I was just zoomed out as wide as things would go. Another graph similarly tells the tale on aperture:

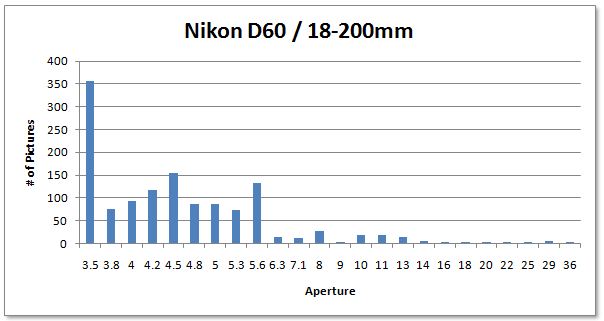

As you can see, I was pretty much shooting at maximum aperture (which ranges from f/3.5 to f/5.6 on the 18-200, depending on focal length) except on a few rare instances – with anything above f/16 being an outright error on my part. Not surprising given how often the kids are indoor in poor light; the D60 was a great camera but not one you’re going to push to ISO 1600 if you can help it. The next lenses I got after the 18-200 were thus fast primes (for other reasons besides aperture), followed by an ultrawide to address the first graph.

Of course, you don’t need to do data analysis to have a pretty good sense of what you’re wishing for. And the most important attributes might not be things you can measure as easily – better sharpness, fast lenses for less motion blur or lower ISO, improved contrast in harsh conditions, more control over depth of field, nicer background blurring (bokeh), or any number of other things. You’ll know what you want. And all you’ll need is a dozen lenses to get it :).

I’ll thus leave it at this simple suggestion – start with a reasonable kit lens like the 18-105, see what you’re really doing, then decide on the more expensive stuff. You can always sell the kit lens later, but you’ll learn what you need because nothing you read on the web – including what I’ll post next – is going to be exactly what YOU need.