Photography

-

Umbrellas are for rain!

I was never a big fan of flash photography. When I got my first DSLR, the D60, I got the most basic available flash with it (the $100 SB-400) so that at least I could try and bounce light off the ceiling, and avoid the reflections and highlights that are inevitable when you flash something head on. I greatly preferred not to use flash at all, but the high ISO performance of the D60, and relatively low speed of the 18-200 lens I used exclusively on the D60 didn’t really make this possible. Indoors, flash was required, though fortunately the SB-400 was a cheap and competent performer. With the D60, 34% of the pictures I took used flash.

The D90’s improved high ISO looked like it would allow me to avoid flash even more, especially because it coincided with getting my first prime lenses, the 50/1.4 and 85/1.8, which do much better in low light situations. But this was mitigated by a couple of things. First, besides being relatively dark inside, the quality of light in our home was poor – ISO aside, things looked better and colors looked more natural with flash. Second, Greg convinced me I should get the better SB-600, which I did; the ability to bounce at any angle and remotely trigger the flash from an off camera position caused significant improvements. Thanks Greg! With the D90, 40% of the pictures I took used flash.

Moving to the D7000 offered even better high ISO performance, but was so clear at ISO 100 that staying low using flash was also appealing. Most of my time with the D7000 has seen in paired with the SB-600, though I did recently go to the marginally better SB-800 (which also provided two flashes in total), after picking it up in that lot sale I mentioned earlier. So far, I’m a good bit lower at 33.5% flash with the D7000, though this is artificially low because I spent winter (usually a high-flash situation) in Asia, often outdoors, with flash not being necessary. So interesting that my flash use seems more or less consistent!

One thing that didn’t change, though, is where I used flash – almost all indoor photos, if light was poor, used flash, and virtually all outdoor photos did not. Fill flash even outdoors can be recommended, but I rarely used this for three reasons – it’s usually head-on (no walls to bounce off outdoors!) so it has that direct flash look I don’t like, it adds too much bulk if I’m not carrying a camera bag (which I usually don’t), and perhaps because of different light temperatures, I just never liked the actual color that was created.

This past weekend was the first real exception to this rule; Wen and I dragged some flash gear to Edwards Gardens to try things out, and the results were interesting! We brought the umbrella I got recently (and had only used it to shoot the pictures of the Lensbaby I mentioned in this post), but with the top removed for use in shoot-through mode, paired with an SB-800. It’s a matter of taste, but I liked the result:

An unexpected side effect of this was that the output duration of a flash is so fast (typically 1/700th – 1/1000th of a second) that it freezes those ever-moving kids, often much more than is possible with available light shooting (natural light allowed for 1/60th, f/4.5, ISO 200). In conjunction with the awesome sharpness of the 70-200/2.8 used to take the above, the amount of detail captured was pretty stunning (a 100% crop of the eye area):

Greg commented that it looked like the umbrella was too close, and he might be right, though I actually don’t mind the effect and indeed think I prefer it. I actually thought it should be close, both from the few explanations I’ve seen of how people light a scene, and from this very helpful article for beginners by David “Strobist” Hobby, “Lighting 101: Umbrellas” – well worth reading – in which he states a preference for shoot-through umbrellas “because you can bring it right up next to someone’s face for both power and softness“. Of course, just do what you think looks good!

We tried a few other things, like using a second SB-600 from behind to create some hair highlights; this picture wasn’t focused well, but does demonstrate the effect:

A more subdued version of this with Linxi:

It was actually impossible to really adjust this because you had to get lucky to get the kids in the frame at all and to have both flashes fire (with no walls for reflections, the rear flash often won’t fire). Still interesting, though!

You might look at this and say hey, this (and several recent posts) don’t look at all like supposedly non-photographer stuff; walking around a public park with multiple remote-triggered flashes and a shoot-through umbrella seems to cross some sort of “seriousness” line. I’ll comment on this separately at some point, but will just mention a couple of things:

- I agree! This was just a fun experiment, and has zero chance of becoming part of my regular kid-shooting routing. It doesn’t work at all if there aren’t two of you taking pictures, and believe me, Valerie is not going to ever help me with something like this!

- I still prefer natural light, since as a non-photographer I want to capture a memory as opposed to creating a photo that isn’t what things actually looked like. That said, we go out when it’s convenient for the kids, not when the light is good, so having this as an option is a good idea.

- If you already have a flash, a shoot through umbrella is actually just about $25-30, and is actually more portable than a regular umbrella. We did have a bracket for the flash, but didn’t bother with a stand and often just let the umbrella sit on the grass. This is a pretty cheap way to get a lot more out of your existing flash!

Olivia’s reaction to the whole umbrella thing was funny, of course, she was convinced we were just bringing it along because it was going to rain – even though there was barely a cloud in the sky! Of course, then she proceeded to show who’s the boss, by making it rain grass on the umbrella!

-

Index of Photography-related posts

Since I seem to have written way too many posts that are related to photography, I created an index page to organize this a little, since I don’t even know what I said anymore. Hopefully this will keep me from saying the same thing many times! It’s also a menu option on the header.

-

Do we really still need HDR?

Some video Wen sent me – high-speed HDR by NASA using multiple cameras – prompted me to think about this topic again.

The power of the human eye (and the brain behind it) really never ceases to amaze when you consider what it’s capable of. We can see perfectly well on a bright day, but well enough with the same eyes to walk around a dark room at night without bumping into things. At least not too many things. In challenging scenes, like a dim room with a window out to an exceptionally bright day, cameras often fall apart and display a pitch black interior and an over-exposed outdoor scene; but our eyes seem to render this perfectly, at least as far as our brain is concerned – we can see interior details and still see a normal, sunny day out the window. It’s all quite remarkable.

The fundamental problem above is one of dynamic range – when there’s a huge variation between the brightest and darkest parts of a scene, it can be a real challenge for the camera to deal with. The camera has a limited dynamic range, so it basically has to pick whether to capture shadow detail and blow out the highlights (turning everything white), or to capture the highlights and turn everything in shadows to pitch black. One approach for dealing with this which is becoming increasingly easy – and popular – is High Dynamic Range (or HDR) imaging – in which the camera takes multiple shots at different exposures to increase the total range of light values that can be captured. So it takes one shot that preserves the highlights, another that captures the shadow detail, and then combines these later (usually in software, but sometimes in camera).

In reality, the problem is only in part what the camera is capable of capturing; monitors have less dynamic range than cameras, and print has less dynamic range than a monitor. Wikipedia cites 10-14 stops for the human eye, 11 for DSLRs (less for compact cameras), 9.5 for computer LCDs, and 7 for prints. So a lot of HDR is actually about how to map what the camera captured (whether in a single exposure or with multiple) into what can be displayed or printed. How that mapping is done determines whether the end result is a natural looking recreation of how our eye perceives an image – or a more artistic/dramatic interpretation of things. I’m personally not a big fan of the over-the-top HDR style – it’s just not what a non-photographer like me would use to capture their kids! But I must admit that some images produced this way are pretty interesting.

2009

About once a year, I try and generally fail to produce an image using HDR. In part, this is because I’m a non-photographer – I never carry a tripod (which is important if you want multiple exposures of exactly the same thing), and HDR is so rarely useful in pictures of the family that I’m not willing to spend money on HDR tools. I’m sure my lack of knowledge is a bigger factor, of course. My first not-so-successful attempt was in Yosemite, taking a picture of Half Dome:

I consider the attempt not so successful because the end result is just kind of boring. I hadn’t started doing any post processing on any photo back then, but even so, the above image was sort of flat. It wasn’t a total failure, mind you; the original default exposure for the above scene looked like this:

As you can see, Half Dome itself is blown out beyond recognition, yet the trees are still very dark, and only the reflection looks about right. So I guess the HDR version is preferable for remembering what it looked like being there, even if it’s not a particularly compelling photo. Of interest might be that I used a free tool that you can find and download online, called Qtpfsgui, to create the above. It was pretty straightforward to use, and offered a lot of different tone mapping options. I’m sure that it’s possible to produce better results than the above by using the tool more effectively than I did. It’s a good cheap way to give things a try!

2010

My 2010 attempt came as I was boarding a flight from Tokyo back to Toronto, as the sun was setting. As with the above example, I only even thought to try HDR because without it, everything was a silhouette against the setting sun:

Besides still being boring, the above fails for another reason – once you bring up the detail in the shadow areas, all the reflections off the glass I shot through become painfully obvious. Since this was literally after showing my boarding pass and on the way to the plane (not the one pictured, mind you), I didn’t really have a chance to get a better picture, go flush up against the glass, etc. And as usual I had no tripod so I was just balancing the camera away from the window itself. For this 2010 attempt, I had gotten suckered into buying Photoshop CS5, which has HDR capabilities – this was my first attempt to use it for that purpose. It was easy to import things; however, I found that the options for tone mapping the HDR were very limited, and I couldn’t produce any sort of interesting results with it. Oh well!

2011

On to 2011! A couple of weeks ago, I was in Naperville, IL – my company has a big office there – and went for a walk since I had to fly in the day before to make an early morning meeting. Another too-much-dynamic range scenario came up but this time, without something to prop my camera up on, I tried doing some hand-held HDR in spite of my past failures. The original, default exposure image was as follows:

The processed image looks a good bit different – and overall, I like it much better:

However, as you probably guessed from the title, this isn’t the story of how I fell in love with doing HDR. Indeed, while I took 3 handheld exposure bracketed shots of the above, trying to using Photoshop to do HDR with the image failed miserably. First, without any sort of support, the alignment between shots was off by enough that Photoshop’s “auto-align” feature didn’t do a great job at putting things back together. Second,it was windy, so the leaves and especially the flag was notably different between shots. And finally, I couldn’t tone map things in an any reasonable way using CS5 (my lack of knowledge again, I’m sure).

So what’s the above then? I took the middle exposure in what had been intended for HDR use – and applied a large dose of local adjustments. Essentially, I darkened the sky and increased its clarity, brightened the foreground, especially brightened the middle column of stairs, added a little vignetting, and a few other things. It was actually quite time-consuming to do this; the sky needed about -1.5 stops of adjustment relative to the foreground, but when you make adjustments that big, if you cross even slightly into the building, you see a big black splotch; if you don’t come right up to its edge, you get a noticeable halo. The above isn’t perfect, but it’s good enough for me!

The above is possible for one simple reason; the dynamic range of modern DSLRs is simply awesome. The D7000 has 13.9 stops of dynamic range at ISO 100; if you compare that to the 10.3 stops at ISO 200 of the D70 (the great-grandparent of the D7000, released 7 years earlier), it’s like having +/- 2 stops of exposure bracketing on every single shot. If there’s enough light to shoot at base ISO, there is just so much to work with that doing HDR just seems like an unnecessary nuisance. As long as you shot in RAW, that is; with JPEG you’re stuck with the first image!

Now, if Lightroom could import multiple RAW images into a single HDR image and then let you do all the usual adjustments, that would still be a real win; sometimes, you don’t have enough light to shoot at ISO 100, or you have more dynamic range than the scene above. But for the most part, I just can’t see myself using any dedicated HDR tools or the built-in HDR functionality in CS5, when the natural dynamic range of the D7000 combined with some local adjustments seems to do all I need!

-

D7000 Settings

Directly or indirectly, I’ve mentioned my friend Herman a couple of times. First in discussing the D90 vs. D7000 (and recommending the D90 for most people + extra accessories), and then again in the whole discussion on lenses in which I said most people should really not buy full frame lenses on crop cameras. Well, the advice clearly didn’t work since Herman ultimately decided to go with a D7000 + 24-70 + the 80-200 that I upgraded from. Well, I tried!

Since Herman has bugging me incrementally for my settings, as if there’s some magical way that I set the camera to prevent my pictures from being blurry, I thought I’d just document them once and for all to avoid future questions.

In the M/A/S/P post from a while ago, plus the first in the series of pages I wrote on Shooting for non-photographers, I actually covered the rationale behind the “main” decisions I made, namely:

- Shooting RAW (NEF), so that I can fix mistakes later;

- Using Aperture Priority mode most of the time, since in most cases aperture has the most direct impact on what your pictures look like;

- Enabling Auto ISO (except when using flash), with a maximum ISO of 3200 for the D7000, and a minimum shutter speed that is the higher of:

- What’s needed to avoid blurriness due to camera shake, typically around 1/focal-length (less with VR lenses)

- What’s needed to avoid unwanted motion blur, typically around 1/80 or 1/100 for still subjects and 1/200 – 1/500 for moving subjects

I guess there are a bunch of other settings, here’s what I change from the default values:

- Main settings (not in menus)

- Single point AF (AF-S), with manually selected focus point; I just find it easier to focus and recompose, but this is situational

- Exposure compensation -0.3 or -0.7 for outdoors/high contrast; 0.0 for indoors. The D7000 doesn’t have as much headroom to recover from over-exposure as the D700, but it has really low noise at ISO 100 – so I prefer to bump up exposure as necessary when processing vs. finding that I blew highlights irreparably.

- CL (continuous, low speed) shooting mode by default

- Shooting Menu

- File naming -> Custom name (MS7 for my D7000), to easily tell my pictures vs. stuff E-mailed to me named DSC_0001.jpg

- Role played by card in Slot 2 -> Backup

- ISO sensitivity set to Auto-ISO, max 3200, shutter speed as needed

- Movie settings -> manual movie settings -> On (I don’t like ISO changes mid-video)

- Custom Setting Menu

- a7 Built-in AF assist illuminator -> Off

- d1 Beep -> Voume Off

- d2 Viewfinder grid display -> On

- d3 ISO display and adjustment -> ISO

- e1 Flash sync speed -> 1/320 s (Auto FP). This allows you to go above the default 1/250 sync with a flash like the SB-600/800; you get reduced output but for fill flash on a bright day, often quite sufficient.

- e3 Flash control for built-in flash -> TTL in some cases, but usually Commander mode even if I’m holding the SB-600/800 in my left hand. Getting the flash off camera helps a lot!

- f1 Light switch -> Info

- f3 Assign Fn button -> Access top item in my menu

- f5 Assign AE-L/AF-L button -> AE lock (hold); I find this better than holding the button down, especially across multiple shots, but watch out in case you have AE-L hold on and don’t realize it!

- f8 Slot empty release lock -> Lock, just to prevent my own errors!

- My Menu

- #1 = ISO sensitivity settings. In conjunction with f3, I can press the Fn button and change minimum auto-ISO shutter speed quickly. Not as quickly as I’d like, if you recall my M/A/S/P post.

- #2 = Flash control, for switching between TTL and CMD. I press Fn, back, down, OK, and I can adjust this easily. Though I’d rather assign the preview button to My Menu # 2 instead.

I have been trying a more radical setting using the ‘U2’ mode, in which the AE-L button maps to AF-ON and the shutter releases immediate, and in which 9-point AF-C mode is used, but I’m still getting used to it.

I don’t think my settings are anything special, just personal preferences, but Herman has this odd belief that the camera comes configured to make fuzzy pictures till you find the magic settings. Sadly, even if he uses exactly what I do, he’ll discover there are no magic settings :).

-

31 Days Later

I’m back from China, and just in time for the Victoria Day weekend! I’ll post some thoughts and pictures from China later – but first, I just found the contrast in weather that we experience here in Toronto in a 31-day timespan to be pretty interesting. We went to the zoo just over 4 weeks ago, and suffice to say it was cold:

They may look nice and warm, but the reality is, we were a little under-prepared and didn’t bring gloves. Luckily, ingenious kids are more than capable of deriving a makeshift solution to the problem – Linxi figured out how to help Olivia with the no-gloves issue:

Just 31 days later, and our trip to the zoo was looking noticeably different:

In fairness, there was a downpour of rain while we were at the water playground inside the Toronto Zoo that almost sent us home; fortunately we stuck it out and things were quite nice after that.

I talked before about having wide angle lenses, and I’m sure glad I did in China – more on that later – but the one place in the world where having the 2.0x teleconverter attached to the 70-200/2.8 (making it effectively into a 140-400 f/5.6) is useful is the zoo. I used this combination on the D3, but Wen also tried it out on his D90 (the crop factor of which gives it effectively 600mm of reach!). It was quite effective for getting up-close shots of animals while still being far enough away to avoid any danger of being eaten, or stomped (both are at the maximum reach of 400mm):

The tiger, of course, was behind a cage – but with that kind of zoom, you just don’t even see the out-of-focus cage grill that’s in front of the camera. With an elephant, 400mm is so much reach you don’t even get the full elephant anymore – but you do an get an interestingly detailed cropping of one (as always, click for a bigger image):

I’m not sure I’ll use the TC all that often, since it’s at odds with my non-photographer goals of really just taking pictures of the people around me, but it’s certainly a better way to get to 400mm than the $10,000 Nikon 400mm f/2.8!

-

Trying out a Lensbaby

Besides the various gear and all those backpacks I mentioned picking up in a prior post, one of the miscellaneous items we got was a Lensbaby lens (for Nikon cameras). Whereas normal lenses have a goal of keeping the entire image as sharp as possible, the design of the Lensbaby is very different – you selectively focus on only a particular part of the image. If, unlike me, you’re artistic, then you can probably achieve the cool photos that they display in their gallery. Otherwise, you’ll probably conclude that you’re not going to practically be able to use the lens, and you’ll give it away or sell it – which is indeed what we’re now trying to do. If you’re interested, let me know!

Still, it is a little interesting to play with. Besides selective focus, you can also use oddly-shaped aperture disks that control what the out-of-focus highlights look like. It’s sort of counter-intuitive, but if you put some sort of cut-out in front of your lens, it doesn’t put a frame of that shape around your picture, it actually just controls what the out-of-focus bright spots look like. Here’s a shot out my window at night, with Bahamut in the foreground, using a standard Nikon 50mm lens:

The lights in the background (mostly streetlights) look like 7-sided polygons, because the Nikon 50mm f/1.4D used above has a 7-bladed aperture diaphragm with straight blades (which is not well suited to this kind of shot; the 24-70 would have produced nicer rounded edges, for example). But throw in selective focus, and a heart-shaped aperture for the Lensbaby, and it looks like this:

You may need to click to get the larger image and zoom in on the head to see it clearly, but the head is mostly in focus whereas the rest of the figure isn’t. And the background is now nice friendly heart shapes. I think the lens could be interesting if used correctly, but it’s incredibly manual, and thus ill-suited to fast-moving kids.

Now, a reason for posting this is that while I didn’t get a picture I liked with the Lensbaby, I fared a little better getting pictures of the Lensbaby. Here’s an embedded SmugMug gallery of the shots of the kit, looking a little better than past efforts to take pictures of equipment – this still doesn’t show in an RSS reader, unfortunately; if you click on it in a browser it will take you to a SmugMug gallery that has the full-sized shots:

There’s still so much camera gear in my place – the above was taken with the D3 and the 105mm VR lens I bought recently – that I guess I don’t have much of an excuse for poor shots, though it still took some learning to get the above. I’m lucky the Lensbaby kit is actually pretty small, this made it a lot easier to photograph. The biggest difference was definitely having two flashes (previously, I only had one), and the umbrella to get more even light (you can see the reflection of the umbrella in some of the above). Still, the background is a combination of the projection screen we watch movies on (or used to, before kids), and my wife’s jacket turned inside out. Hey, whatever works, right?

-

Backups and Backpacks

I finally got around to writing the last page in a series of topics related to how I handle pictures, from shooting through Backups and Sharing. Intended as always for the non-photographer like me! The short summary of the page is: SmugMug is great, go get an account!

No matter what you use, you really do need to back things up, though. Disks fail, it’s only a question of time. In an earlier post on Storage that I wrote when finishing the page on how I manage storage within my home, I made fun of Intel for pushing solid-state disks (SSDs) as a more reliable way of storing important data than standard magnetic disks. So it was interesting to see this blog post from Coding Horror describing the failure rate of SSDs:

Portman Wills, friend of the company and generally awesome guy, has a far scarier tale to tell. He got infected with the SSD religion based on my original 2009 blog post, and he went all in. He purchased eight SSDs over the last two years … and all of them failed. The tale of the tape is frankly a little terrifying:

Jeff goes on to conclude that he’ll buy SSDs anyways because they’re so darned fast – and I completely agree with this. If you plan for disk failure, it’s really not a big deal when it actually happens. My thoughts on how to do this are in the article linked in the first line, but however you do it, make sure you back up!

What does this have to do with backpacks? Absolutely nothing, except that they both begin with “back”, and I’d been meaning to write about an interesting experience from last Saturday that resulted in having six more backpacks by the end of the day than the start of the day. Though I have more photo equipment than I need (and what I really need is to learn to use it better), there’s always a few more things that it would be “nice” to have (like that macro lens), so I tend to check Craigslist once in a while to see if something pops up at a good price.

I noticed a posting of a big lot of items; they were offered individually but with an invitation to take the whole lot. I had expressed interest in one flash and one umbrella (for lighting), and forwarded it to my friend Herman who was also looking for a couple of items on the list. After making the initial offer on a small subset of the items, I started to strongly suspect the only way to get any of the items was to make an offer for all of them – and indeed this turned out to be exactly what the seller was looking for. Saturday turned into a crazy day of going to a wedding ceremony, closing a deal on the whole lot of items via E-mail in the midsts of that, rushing to bank as soon as things were over to start getting the cash, heading to badminton in a suit to get the courts & nets set up, rushing to more bank branches (due to withdrawal limits at a single branch), going back to organize the badminton club, heading from there to the wedding reception in the evening, and then finally – by 11pm – heading to inspect and pick up the equipment.

I should have taken a photo of the entire lot, but it included a D3, 14-24, 24-70, 70-200, 3 SB-800s and an SB-900, a macro flash kit, two umbrellas, and a host of other items. As advertised, it included 3 camera bags; the seller was generous and decided to just part with all the camera bags he had. And he had 7 of them, 6 of which were backpacks. It was a really good deal for the entire lot of equipment – but the total amount of stuff was insane, especially since I just wanted one flash and one umbrella. Equipment can’t make you a pro, but I doubt anyone would believe the non-photographer story were I to walk around with this:

That’s the Nikon D3, with the 24-70/2.8 lens, and the macro flash kit. My wife Valerie said she would not be willing to walk with me in public if I was carrying that thing. Sadly, I only set it up for fun, as I didn’t have any of the specialized batteries needed to power the flashes – and later in the day, the whole macro flash kit was on its way to Asia with my departing mom, for use by my professional step-father. At least it’s in much better hands than mine!

And if you need a photo backpack, let me know.

-

How Wide is Wide Enough?

Despite the rather extreme length of the prior post on lenses, some parts were heavily abbreviated. In particular, in the section considering whether it’s worth thinking about the upgrade path to full frame when buying lenses today, I omitted one huge reason for not doing this – you can’t get wide enough on a crop camera (DX) with full frame lenses alone. I did mention that there are really no wide primes for crop cameras (on Nikon), but this is mostly true of full frame zooms also.

Setting aside the very special purpose (and very expensive) 14-24/2.8 for a moment, it’s temping to say “not true, what about the recent 16-35/4.0 VR?” (or its Canon L equivalent)? After all, the widest all-in-one zoom is the 16-85mm – so this gets at least as wide, right? On the surface of things, this is a true statement, and indeed 16mm (or the more standard 18mm starting point for most kit zooms) may be as wide as you need to go. Thus, the titular question – how wide is wide enough?

The problem is that a lens like the 16-35/4.0 is an ultrawide lens on full frame, but merely covers the wide end of the range on a crop camera (24-52mm equivalent). And here’s where you’re stuck in a “heads you lose, tails you also lose” situation:

- If you don’t need to go wider than 16mm (on a crop camera), then it seems like you’re set. But then as soon as you do upgrade to full frame, you’ll find you spent $1000 on an ultra-wide full-frame lens that covers a range that you decided you didn’t need. Oops!

- If you do need to go wider than 16mm, then no full frame lens will do that for you. Sure, the 14-24/2.8 will get you a hair wider for $1800, but that’s really not a viable solution. Eventually, you’ll break down and buy a DX lens that won’t work on full frame – and also might not complement your other choices of full frame lenses.

The core of the above issue is that while lenses like the 24-70 are useful (IMO) on a crop camera, and the 70-200 even more definitively so, an ultra-wide full frame zoom covers an awkward and narrow range on a crop camera. The “pro” recommendation to skip midrange zooms and go for a combination such as 16-35/4.0 + 50/1.4 + 70-200/2.8 is thus great for full frame, but significantly lacking when used on a crop camera.

Still, full frame aside, the question remains – how wide is wide enough? 18mm? 16mm? Less? This is a very personal question. I believe that most non-photographers don’t really have a need to get below 18mm – and certainly not below 16mm. It’s at least advisable to read something like Ken Rockwell’s article “How To Use Ultrawide Lenses” before deciding, since as he notes it’s tough to get good results. And frankly, when you want people in the picture (which is often a main goal for the non-photographer) it’s even more difficult to use an ultra-wide well.

I’ve still got a ton to learn in this department, though I will note that for the non-photographer, “getting it all in” (criticized in the above article) can still be quite useful even if it creates a somewhat ugly picture. As an example, consider all those indoor kids birthday parties:

I actually picked this image, shot with the Nikon 10-24, because (a) it was an enclosed space where it would have been impossible to capture the whole group @ 18mm, and (b) it shows how brutally distorted people at the edges of the frame become (not due to lens errors, just due to perspective).

Given the effect on people, I find I use the ultra-wide more often to capture places I’ve been rather than people (unusual, since about 80-90% of my photos are of the people I’m with). Still, over time, you get to learn how to incorporate people into the frame – though that’s something I’m still working on.

Here’s an experiment creating an embedded SmugMug gallery of wide angle shots; everything here is wider than 18mm and most shots are closer to the 10mm side of the equation. You won’t see this in your RSS reader (you’ll have to open the post on the actual site to see this); clicking the image outside the buttons will take you the gallery itself on SmugMug:

Almost everything above was shot with the Nikon 10-24 which I own, but #16 and #17 were with Wen’s Tokina 11-16 – a very nice lens that’s a bit more restricted in range, but faster (f/2.8 vs. f/3.5-4.5) and I think perhaps sharper than my copy of the Nikon. The Sigma 10-20mm was another strong contender. Overall this category of lenses is pretty pricey, but quite a bit of fun – you’ll be able to capture your experiences in a somewhat unique way!

-

Lenses: The Eternal Question # 2

The last post introduced the unsolvable question of picking the right lenses, suggested starting with what you have / a kit lens, and using the amazing capabilities computers give us to understand how we are using what we have. You can’t tell what you would have used if you had it, of course, but it’s still a good starting point. At least, it was for me.

Part 2: Understand The Basic Approaches

Having read a lot of online discussion before getting my initial D60 + 18-200 – and far more after jumping in – I came to believe that everyone comes at things from a particular perspective, and usually makes recommendations from that perspective as to what is “right”. Of course, they’re all right – everyone is recommending what genuinely works for them, and your task is to figure out which recommender feels closest to you.

However, this discussion is often a little stacked; those serious enough to head online and give advice to others (myself included if you count this as such) are almost by definition more serious about photography, and this often weights the opinions that you’ll see in a particular direction. Thus, if you’re a beginning non-photographer (that is, just moving beyond a compact/cameraphone but certain that your intent is better memories, not selling images or launching a new career), it may be helpful to understand how these approaches apply to you.

Note that these approaches are not mutually exclusive, but it’s typical to at least start with one or another.

The examples here are all Nikon specific, but I’m pretty sure anyone with knowledge could translate this directly into Canon or other terms pretty easily.

Approach 1: One Lens to Rule Them All

Just because you can change lenses with a DSLR, does not mean that you have to. The benefits of near-instant response time when you press the shutter button, fast auto-focus, better image quality especially in low light, and others apply as much regardless of whether you have one lens or twenty. Indeed, anyone with a DSLR wishes that there was the one universal lens that did everything they need, but alas, no such thing (yet).

Occasionally, you’ll see the philosophy that a single fixed (i.e. can’t zoom) wide angle lens is all you need. In fact, anyone coming from a cameraphone as their main equipment will likely be quite familiar with this idea, and indeed by adjusting your perspective it’s possible to achieve quite a range of results despite a fixed focal length. An example of this is the attractive, retro-styled Fujifulm X100, pictured below (the image is Fuji’s, and links to their X100 site). I can’t bring myself to pay even close to the astronomical $1,200 asking price – even though I like the concept, and like the controls (which I just realized are almost exactly what I asked for in the M/A/S/P post):

More often, proponents of the one-lens approach recommend a zoom that covers a decent range from the wide end through to at least a mild telephoto. It’s much more typical to find yourself wanting something wider than it is to lack reach when dealing with one-lens situations (especially on anything less than a full-frame camera, which an all-in-one shooter is almost certainly going to be using). S0 18mm (on crop sensors) is usually the minimum you see here. Nikon makes a whole boatload of lenses for this purpose; the more popular current ones are:

- 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 DX VR – $100 kit lens that adds very little to the cost of the camera. It’s wide enough, but it’s reach on the long end is pretty limiting, which is why it’s designed to be paired with something like the 55-200mm or 55-300mm telephoto zooms.

- 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6 DX VR – $200 kit lens that just about doubles the reach of the entry level kit lens, giving you a very usable range. I recommended this as a good starting point to figure out what you really use.

- 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 DX VR – $800 “superzoom” that covers an absolutely enormous range, but comes with a hefty price tag to match. This is the only lens in this category that I’ve personally owned.

- 16-85mm f/3.5-5.6 DX VR – $700 lens that gets 2mm wider at the expense of some reach – but that is respected as having the best image quality in this class.

- 24-120mm f/4 VR – $1200 full-frame lens that gives similar coverage to the 16-85mm on an FX camera; there’s also a smaller, cheaper, variable aperture version. Neither version seems to be too popular with users.

- 28-300mm f/3.5-5.6 VR – $1050 full-frame lens that’s equivalent to the 18-200mm but for full frame. Again, only viable on a full-frame camera (28mm is not nearly wide enough on DX), where it’s unlikely that this will be your only lens.

I only mention Nikon offerings above, but many 3rd-parties like Sigma, Tamron, Tokina, and others have decent offerings as well, usually for much less money than Nikon (kit lenses aside).

The major appeal of this category is that it’s convenient (no changing lenses around and missing things while doing so), relatively light (vs. carrying multiple lenses), and inexpensive. What you give up for this is wider apertures – almost all of the above are zooms that hit f/5.6 on the long end – and in most cases, some image quality. Bokeh (background blurring) in particular tends not to be great on almost any lens in this category. And while the range of focal lengths is good, you don’t get that wide, or that long.

I started in this category, before growing out of it. Per my last post, I think it’s a great place to start as you learn your way around and figure out what you really need. In my case, I tried and loved the increased sharpness of primes, which was my first step out of this camp. Also, in the D60 era, going anywhere above ISO 800 noticeably reduced image quality, so I tended to try and stick to ISO 400 or below, and this meant the lack of wider apertures hurt quite a bit.

I think my personal error was not starting with this category – it was definitely the right category for me at the time – it was that I should have gone with a $200 kit lens instead of spending four times as much on the 18-200. The 18-200 is supremely convenient and I still take it when I need a one-lens solution, but with the difference in price I could have been experimenting with primes and different lighting options instead. Or having some really nice meals.

Still, there’s many pictures of the family – including nearly the entire first year of Olivia’s life – that the 18-200 captured for me, and despite having acquired quite a bit more gear it’s still a definite candidate when I’m getting on a plane and don’t want to bring multiple lenses along. Here’s a rather poor picture of my actual lens – highlighting how what a pro photographer knows is still vastly different from what I know:

Telltale non-photographer signs above (besides the lack of overall quality):

- Using a blue polka-dot baby blanket to reflect some light back from my one and only external flash, which you can clearly see in the front element reflection. Sorry, it’s all I had!

- An F75 film SLR standing in as an “arm model”, like the owner of an anonymous arm used in a Rolex commercial who is there just because they need something – anything – to attach the watch to. I’ve only got one DSLR body!

- Black background with the plastic tripod visible. I have nothing resembling a studio (and don’t need one, as that’s not where my kids play); the above was taken in my kitchen!

Approach 2: A Set Of Primes

Don’t worry, this one isn’t a math question about prime numbers. Prime lenses are just another way of referring to lenses that operate at just a single focal length (like the Fuji X100 above) and don’t zoom. If you want the subject smaller, you step back; if you want the subject larger, you step forward. Of course, stepping backwards isn’t possible in an enclosed room, and stepping forward when you’re shooting the Grand Canyon can certainly bring you closer to its rock formations in a hurry, but probably not in a manner that you’d like. Plus if you’re shooting landscapes, you’ll need a fairly impractical number of steps to adjust your perspective, but hey, if you’ve never climbed Everest, go for it!

How many primes you need depends on what you shoot and how many of those aforementioned steps you’re willing to take. Nikon seems to think that the answer is “as many as you can carry”, and thus you see 14mm, 16mm, 20mm, 24mm, 28mm, 35mm, 50mm, 60mm, 85mm, 105mm, 135mm, 180mm, and 200mm+ primes available, with the 24, 35, 50, 85, 105, and 200 being quite current. There’s many others in between if you look, like the Nikkor 58mm f/1.2 Noct, which seems to fetch almost $4,000 used. 200mm+ primes are usually rather expensive (thousands of dollars), and bulky enough that only pros with specific needs venture there.

Primes typically give you the best image quality – and historically, a much lower per-lens weight – at the focal length they cover. They are also typically quite fast; few primes are “slower” than f/2.8, and the fastest are f/1.4. A shot that’s ISO 200 @ f/1.4 would be ISO 3200 at f/5.6 – the difference is deceptive, because light absorbed is proportional to the square of the aperture. However, the fixed focal length means you better be prepared to switch lenses!

With that as context, a few comments on going this route as a non-photographer, based on my own personal experience:

- I started with a very standard 50mm prime; I got the 50mm f/1.4D ($350), but the 50mm f/1.8D ($130) works just about as well. On a crop camera, this is actually pretty long – it’s useful for portraits but you’re not going to get a group shot with a 50mm lens.

- I received the 85mm f/1.8D around the same time, and found that this was essentially as long as I wanted/needed to go on DX. I used to joke that if I’m shooting my kids @ 200mm, then I’m too far away from them! The 85/1.8 is a great lens and also only about $350-400.

- A prime lens that no Nikon shooter with a DX camera should be without is the 35mm f/1.8 DX. It doesn’t work on full frame, but it is a very useful focal length on a crop sensor, and produces great results for its low price (now $280 new) and size. I pretty much stopped using the 50mm f/1.4D after this came out; the 35 + 85 combination was just a better match for most things.

- Sadly, the wide end is a real problem if you’re using any DX (i.e. consumer) camera. The widest prime you can economically find is probably the 24mm f/2.8D, and that’s not wide enough on DX. Thus while I liked primes a lot, I got the 10-24mm DX ultrawide zoom to cover the wide end. Thom Hogan frequently calls for Nikon to wake up on this one, and I hope that they listen to him and do.

- If you think primes sound interesting, buy a D90 or above. In fact, with the recently released D5100 having the same sensor and image quality as the D7000, and pretty much every modern zoom having AF-S and working just great on the D5100, one of few major reason to get something better is if you want to use older primes that require a focus motor. The 50/1.8, 50/1.4D, and 85/1.8 all still require that the camera has a built-in focus motor; otherwise, you’ll be manually focusing them.

Nikon has modernized some of their primes recently, but for some reason they seem to think that only people made of money are interested in them (though an upcoming 50/1.8 AF-S addresses this at least a little). Their 3 most recently updated primes – the 24/1.4, 35/1.4, and 85/1.4 – all cost $1700 or more, each. That makes this set containing all three a “bargain” at just 4,900 Euros (photo origin unknown, I found it on Nikon Rumors but Nikon is likely the original source):

So, get a camera with a focus motor and get some older, cheaper primes. Unless you ARE actually made of money.

Approach 3: The Holy Trinity

On a crop sensor, covering the entire range of meaningful focal lengths requires 10-12mm on the wide end, and 200-300mm on the long end. This offers everything you’d need from an ultra-wide perspective through to shooting faraway things (like a bank account that allows you to retire, after buying all this stuff). No all-in-one solution does that, and on crop sensors, no set of primes does that either – and long primes cost a veritable fortune (the 300/2.8 is $6,600).

When I started looking beyond the 18-200, there was a full frame set of three high-end zooms – dubbed “the holy trinity” – that covered a wide range while providing image quality comparable – and in some cases superior – to equivalent primes. Pulling this 0ff was something of an engineering marvel, as prior to this zooms had generally been considered a convenience that was going to cost you in terms of image quality. Not anymore! The only compromise was a maximum aperture of f/2.8, but that’s pretty reasonable for most subjects. There were three members of this “holy trinity”:

- 14-24mm f/2.8G AF-S

- 24-70mm f/2.8G AF-S

- 70-200mm f/2.8G AF-S VR

Even used, each of the above goes for about $1,500, and they’re considered pro zooms. But they’re a benchmark for what you can get without compromise. And they’re expensive particularly because they are full frame lenses. Still, you can come up with much more economical combinations with the same philosophy – an ultra-wide zoom, a mid-range zoom, and a long-zoom. Here’s what I’ve tried or considered in this range:

- 10-24 DX + 24-70 + 70-300 VR. This combination costs a little over half of what the above would cost, and compromises with variable aperture zooms on the wide and long ends, but actually covers a much wider 10-300 range (compared to 14-200 above). This is the combination I own and use, but I can’t recommend it for everyone due to the size & cost of the 24-70.

- 10-24 DX + 18-55 VR + 70-300 VR. Swapping out the expensive pro 24-70 for a kit lens like the 18-55 takes this same approach but chops the price and size of the combination down enormously, which still retaining the 10-300 range. You could also use the 55-300 DX VR zoom instead of the bigger full-frame 70-300 VR, but opinions of the latter are much better than of the former.

- 10-24 DX + 35/1.8 + 55-200 VR. Even better than the above is breaking the rules a little and using the 35/1.8 prime to cover the middle of the range. I’d definitely do this over the above, but it does make the 55-200 (or 55-300) options more appealing to get a bit better mid-range coverage.

In the latter two combinations, the 10-24 DX contributes the largest part of the cost. There are alternatives here, like the Tamron 10-24 (much cheaper, though reportedly lower image quality) or others – and you may not really need ultra-wide coverage below 18mm.

Of course, nothing says you need to go with three zoom lenses. Notable two-lens combinations are:

- The classic 18-55 DX + 55-200 DX pair that provides great coverage, at half the price of an 18-200mm with a little less convenience.

- The 16-85 DX + 70-300 VR pair is something I think would work really well for a lot of people; it’s about three times as expensive at $1200, but both of those lenses are considered to be top notch from an image quality perspective. The 16-300mm range is very decent unless you really want ultra-wide coverage.

Approach 4: DX Now, Full Frame Later

Should I favor (or exclusively purchase) full frame lenses over DX counterparts that only work on crop sensors? This question comes up because almost every non-photographer is going to have a crop camera (anything below the D700 on Nikon, or the 5D on Canon), but will nonetheless wonder if they might upgrade someday – especially if full frame camera prices drop far enough.

In most cases, the answer to this question is: no, you won’t. Why?

- Crop sensors today are really good. When the D3 (Nikon’s first full frame camera) showed up, you’d be hard pressed to go beyond ISO 800 on a crop sensor. Today, you can do ISO 3200 with the same approximate image quality on a crop camera. Resolution (short of the $8,000 D3X) isn’t notable different between crop and full frame sensors, nor are other parameters like dynamic range. Do you really need to get to ISO 6,400 or ISO 12,800?

- Full frame won’t be mass market, and will thus continue to be expensive. If Nikon (or Canon) thinks they can get you for $2,000 a lens for full frame lenses (and they do), you can bet they’re not planning for a $1,000 full frame camera.

- You’ll still wind up with some DX gear that will inhibit switching in the interim.

Despite this reasoning, I still think I’ll go FX someday, and thus I now favor full-frame lenses. This is because:

- I’m too foolish to follow my own advice.

- When I’m old, I think I’d rather have nice pictures to look at (with the 0.5MP eyes I will have), than memories of a nice car or a bigger house, so I’m prepared to spend proportionally more on this, mitigating the cost issue somewhat.

- I already have a decent collection of full frame lenses, and tend to like primes which are mostly designed for full frame anyways.

- I found the images from the D700 I used for a while to be really nice, notably better than my D7000 even with everything else held constant. I don’t know if full frame is a requisite ingredient to achieve this, but despite a 2-3 year technology gap it’s still the best camera I’ve used – and I’m really wondering what it’s replacement is going to do.

Once again, I think the above are all factors that are sort of unique to me, and not true of most non-photographers. Buying for DX is significantly cheaper, and if you go used, it’s not expensive to make the switch if you were wrong!

Approach 5: I Want It All

If you bumble around without a strategy for what approach works best for you, you may wind up staggering around through each of the above, picking up a little gear along each step of the way. That’s exactly what happened to me:

- I started with the 18-200 all-in-one mentality;

- Then I warmed to prime lenses, using the 50/1.4 overwhelmingly, followed by the 35/1.8 + 85/1.8 combination;

- I discovered the DX wide prime hole, and plugged it with the 10-24;

- Around this point in time, my daughter started running – sometimes towards me – and I doubt even a pro could change lenses faster than she runs. I got the 24-70 which quickly became the most popular lens in my collection. Now running kids was slightly better handled – a shot seconds before this was at a very different focal length:

- With the above, I got a D700 (which wasn’t ultimately intended for me), which made clear that full frame was a distinctly attractive possibility to me despite all the drawbacks.

- With the 24-70 as my new favorite, coverage on the long end became more important as I was no longer bringing the 18-200 out; but 70mm maximum is short on the long side. Hence the 80-200/2.8 and 70-300 VR (both of which I have to thank my stepfather for).

At least I can credibly claim that I understand the different approaches to putting a set of lenses together, having tried pretty much all options! That said, this was certainly not the most economic route to get to the set of lenses I most actively use today.

Perhaps I do this to convince myself I’m not a fool for accumulating all this stuff, but a real benefit of having gone through the above is that I now have a choice – every time I head out and bring the camera, I can choose what makes the most sense for that outing. Sometimes, just the 35/1.8 is nice and small, and good enough for the situation. Often, I just bring the 24-70. On a one-day, no-checked-bags trip to New Orleans, it was still the 18-200. Today at the park, it was the 10-24, 35, and 105. Earlier in the weekend, the zoo called for something like the 70-300, which was helpful in getting this shot that I sort of like – he (or she) seems to be wondering what lenses he needs too:

It’s definitely a luxury to have the choices I do – good thing I’m not into cars or boats or something else costly!

-

Lenses: The Eternal Question

The moment you get sucked into the DSLR racket – or even as you consider it – you start the never-ending journey of asking yourself what lenses you need. There’s really no way out of this; even if you bought every lens available for your camera (recommendation: go with something like the Sony NEX-5 that only has a handful of lenses!), you’d still probably check nikonrumors.com to see if anything new came along that you now need. Almost exactly three years ago, I bought my first DSLR (Nikon D60), with a “do all” 18-200mm zoom lens that I never intended to take off the camera. 10 lenses later, I can’t say that this was a particularly accurate prediction.

Still, about half of photography forum chatter seems to be either “what lens should I buy” or “what lenses should I take on a trip to… my backyard”. Amazingly, this question comes up a lot offline too; in one day, I wound up E-mailing my brother about lenses for a wedding his friend asked him to shoot (major pressure for a non-photographer!), and my friend Herman who is getting further along in pondering his switch to Nikon. A little planning here is important, so you don’t wind up like Greg from my work, with a 16-85, 24-120, and 28-75 in a collection of just five or so lenses total (due to the significant overlap). Or like me, with 10 lenses instead of a planned 1.

Lens selection is a 7-way trade-off between focal length coverage, maximum aperture, build quality, price, size, weight, and features (AF, VR, macro, etc). Some of those (e.g. size & weight) are linked, others less so. If the best lens wasn’t highly situational, there wouldn’t be so many of them. This creates the usual photographer vs. non-photographer dilemma; what’s very good advice for an aspiring photographer can be very different from the right choices for a non-photographer.

With that said, how and what should a non-photographer choose?

Part 1: Learn From Yourself

Especially if you’re just starting out, there’s two things hugely in your favor when it comes to choosing lenses:

- A highly competent kit lens is just $150-200 over buying the camera body only and getting alternative lenses separately. On Nikon, you’d get a 18-105mm zoom with VR, which will already far outperform any compact you may have owned. This will be sufficient to learn what you really need, and gives you a good initial range.

- Lenses actually hold their value quite nicely, and as a result, if you ever decide that you want to go a different route, you can often recover close to the full value if your kit lens if you didn’t get the very entry level 18-55mm that wouldn’t be an upgrade for anyone.

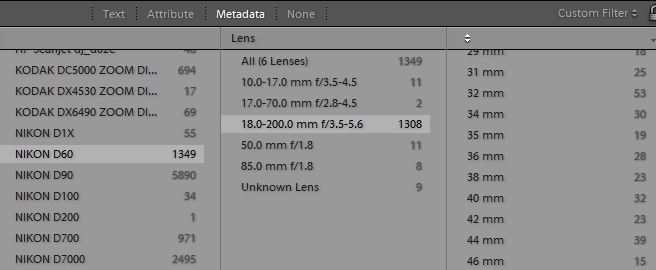

The nice thing about digital photography is that every choice you ever made is recorded somewhere, just waiting to be analyzed – what lens you used, at what focal length, aperture, shutter speed, whether you used flash, ISO, etc. If you use Lightroom, you can filter by meta-information in the library view to get some insight – like what focal lengths you use most often with a given camera & lens:

Now, Lightroom isn’t free (especially relative to a $150 kit lens!), and even if you have it, the above presentation isn’t great. Fortunately, there’s free tools that can extract EXIF information from your JPG files (or directly from raw files). Several are available, but one I’ve used is ExifPro, available at http://www.exifpro.com/; it’s free though if you use it regularly you can buy a license.

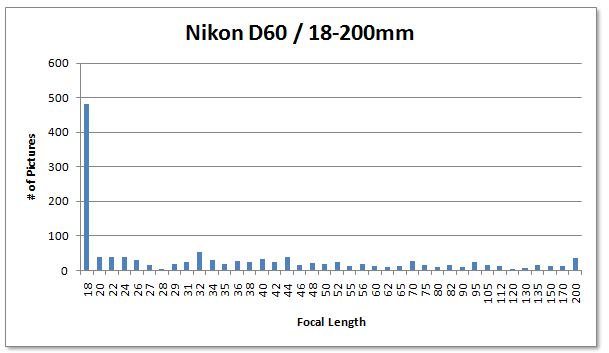

Using ExifPro, I just select all my photos, add columns for camera and lens type, export the EXIF data to a text file, and then use something like Excel to graph your actual usage. In a few minutes, you can have a simple chart like this:

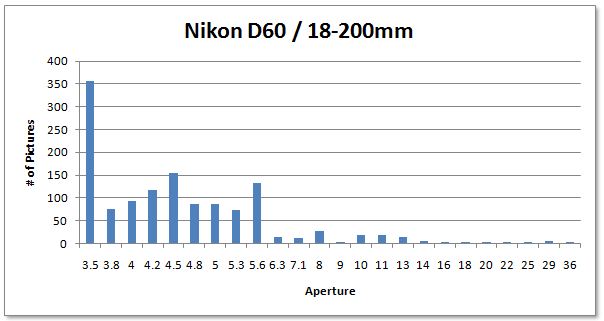

This is my actual usage of my first DSLR, the D60, with “only lens I’ll ever need” – the 18-200 VR. Looking at the graph above, what do you think I bought first – an ultra-wide lens (covering less than 18mm), or a longer telephoto (more than 200mm)? Not hard to guess the answer to that question; I was stunned at how often I was just zoomed out as wide as things would go. Another graph similarly tells the tale on aperture:

As you can see, I was pretty much shooting at maximum aperture (which ranges from f/3.5 to f/5.6 on the 18-200, depending on focal length) except on a few rare instances – with anything above f/16 being an outright error on my part. Not surprising given how often the kids are indoor in poor light; the D60 was a great camera but not one you’re going to push to ISO 1600 if you can help it. The next lenses I got after the 18-200 were thus fast primes (for other reasons besides aperture), followed by an ultrawide to address the first graph.

Of course, you don’t need to do data analysis to have a pretty good sense of what you’re wishing for. And the most important attributes might not be things you can measure as easily – better sharpness, fast lenses for less motion blur or lower ISO, improved contrast in harsh conditions, more control over depth of field, nicer background blurring (bokeh), or any number of other things. You’ll know what you want. And all you’ll need is a dozen lenses to get it :).

I’ll thus leave it at this simple suggestion – start with a reasonable kit lens like the 18-105, see what you’re really doing, then decide on the more expensive stuff. You can always sell the kit lens later, but you’ll learn what you need because nothing you read on the web – including what I’ll post next – is going to be exactly what YOU need.