Photographers vs. Non-photographers

I’ve made a decent effort – perhaps to the point of being annoying – to be clear that I consider myself a non-photographer. Initially I used the term “amateur photographer”, but I realized that this wasn’t distinct enough – some “amateur photographers” go on international trips just to shoot pictures and hone their craft. That’s not the image I was trying to conjure up, so I switched to the term non-photographer.

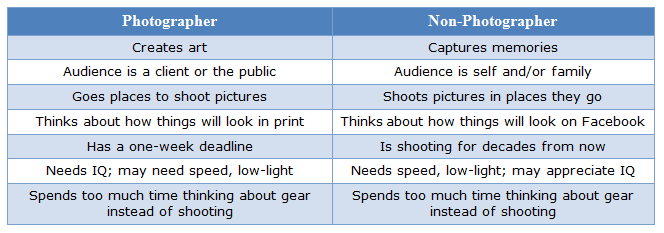

I wrote a brief post some time ago titled “Amateur vs. Enthusiast vs. Pro” (before adopting non-photographer) to better state what I meant by this, but I always intended to revisit the topic and be a little clearer about the differences. I feel especially compelled to do that now, as despite lugging around the professional D3 and even some pro-oriented glass, I’m still definitively a non-photographer. What do I mean when I say this? Perhaps this table will help:

Each row in the table (except perhaps the last) requires a little elaboration, which is below…

Art vs. Memories

This one is fairly self-explanatory. In most cases, photographers are trying to create art – or at least something artistic. Keep the image simple, watch the lines, think about the story it tells, etc. Much depends on the nature of the photographers work, of course; if they’re shooting hundreds of graduating high school kids, they’re probably a little limited in the latitude they have for artistic expression, but we can all imagine the aspiring photographer that’s hoping to capture an iconic shot that resonates with viewers.

On the other hand, while the non-photographer might have some artistic inclinations, their primary goal isn’t creating art, but capturing life as-is (though this can be its own art form). This means that subjects often aren’t posed in an appealing manner or dressed up for photo day; and if you’re planning your kids birthday party as opposed to planning a photo shoot, the first priority might be the flavor of the cake, not positioning the lighting equipment you couldn’t possibly bring. But generally, if you capture the scene (and its emotions) as you remember it, the photo will have meaning to you.

A memory, but definitely not art!

Shooting for You

Photographers do generally try to produce images that they themselves like, of course, but if you’re the only one who sees beauty in your own photographers, you’re probably not going to survive in the profession for very long. If you’re a pro, you’re often shooting directly for a client or a job, and you’re naturally pretty concerned with making the client happy – as should rightfully be the case. Even amateur photographers crowd Internet forums, showing off their often impressive shots, asking for comments & criticism, and seeing what others think. Sites like Flickr became enormously popular for this. Amateur photographers can now even make a few bucks by taking some nice shots, and listing them with stock photo sites, in the hopes that it will catch the eye of someone who wants to use it in a web site or print campaign or something of the sort.

By contrast, a non-photographer is truly shooting for themselves, capturing memories intended for viewing many years down the road – by family and friends, not by general members of the public. They’re not too concerned with what others think of the pictures, as long as it’s meaningful to them. Whereas a photographer might search for a caption that captures the essence of the photo in a few short words, a non-photographer is more apt to attach a description noting that this was at John’s friends Bob’s 3rd birthday party – so that in a decade, the photo still makes sense.

If non-photographers really think hard about what shooting for a future version of themselves means, it can also drastically change what they do. When I recognized that with my original approach (keep everything), I’d wind up with perhaps 100,000 pictures by the time I reach old age, some of which were blurry, and many of which were of exactly the same thing, I started deleting aggressively. If I took a few shots of the same thing, I started picking the best one and throwing the others away. This is exactly the opposite of advice I’ve read from photographers suggesting that you should keep every shot, because you never know when a client might want a different angle. Very true for the photographer, but when I’m 80, I’m not going to be going through a lifetime of shooting using Lightroom and trying to get the most out of a 27 year old photo. I’m selecting now, for the old version of me later. I also started tagging and captioning – knowing that in 20 years my memory will have fade,d but that even a short description might allow me to recall what I was looking at.

This is even more important if you shoot not for yourself, but for your kids. They’ll have no recollection of the actual pictures, at least till they are older, and will be far too impatient to sift through thousands of the same shot. So for their sake too, cull and organize your collection. Doing so will be a gift to them.

This picture wasn’t shot with Motorola in mind as a client

Goes Places vs. Places We Go

If you’re a landscape photographer that just admires Ansel Adams, then chances are that you have or will make a trip to Yosemite at some point in your life, with the goal of capturing some of the magic that he did. My step-father is a pro, and once they had a theme for a project like the annual calendars they used to shoot for National/Panasonic – say, the natural beauty of Malaysia – they’d start planning out the places they could go to get the shots they wanted for that year’s calendar. The point of the trip was getting great photos. Great photos, great trip. Of course, there’s often a lot to enjoy about those trips, and I was fortunate to participate in some of them. Indeed, a nice thing about this kind of photography is that you find yourself in places that are beautiful even if you aren’t carrying a camera.

By contrast, a non-photographer never goes somewhere for the purpose of taking pictures. Rather, they take pictures of the places that they would have gone even in the absence of having a camera. The camera is an accessory, an add-on that lets you take a part of a place with you so that you can remember it later. Even when traveling for vacation, a non-photographer will likely have shots of a visually uninteresting but culturally significant places, whereas the photographer is likely to skip such places (or at least treat them separately from their primary shooting).

This isn’t just about the places either, it’s also about things like times of day. For many kinds of photographers, the “golden hour” just after sunrise and just before sunset is the perfect time. For non-photographers, the “golden hour” is more likely to be that time after your kids finish their nap but before you have to start planning for dinner. As I mentioned in the aforementioned post on this subject.

Further, in a given place, the photographer is usually trying to capture the essence of a place – perhaps in a unique-place if it’s often photographed. The non-photographer will often want a shot that says “I was here”, or that gives them something to conjure up the memories of being there.

Print vs. Facebook

If you ever start a discussion remotely resembling “how many megapixels do we need” with an actual photographer around, you’re bound to hear a particular question – what’s the largest you print? Indeed, the megapixel debate is an unnecessary one, with cameras on the verge of outperforming most available lenses – and per-pixel quality counting much more than number of pixels in making a nice looking image. But print simple isn’t the medium for non-photographers to nearly the extent that it is for actual photographers.

Sure, many non-photographers still make prints – some 4 x 6″ prints for an album, perhaps something a little larger once in a while. There’s even a good variety of consumer-grade photobook services that let non-photographers create decent looking books. Still, I think the primary consumption mechanism for most non-photographers is via a computer (or mobile device) – that’s where they’ll probably browse their own collection, and it’s also how they’ll share photos with the rest of their family.

This has a few implications. First, absolute resolution (and in turn, absolute sharpness) is a little less critical, especially since most consumer displays aren’t that high resolution. Second, color correction might be imperative for print, but it’s less relevant for PC viewing simply because it’s an losing battle – you might pay big bucks for a high-end monitor and have it properly calibrated, but odds are, none of your family/friends are going to do the same – and tuning for “accuracy” might ironically make their viewing experience worse.

I mention Facebook here by proxy; what I really mean is that people will share photos online. Some non-photographers will be perfectly happy with a Facebook-sized photo. Personally, I pay for SmugMug because I think it’s vastly nicer for sharing photos. I upload original resolution images, and friends/family can download those to make prints if they so wish.

You might think that the above all adds up to a suggestion that the non-photographer should really be OK with a relatively low pixel count and sharpness level (other things like contrast and bokeh are important regardless of resolution). And that would have a semblance of truth, if not for…

Today vs. Tomorrow

Only a few photographers are taking pictures with the explicit goal of creating a masterpiece that will transcend time. Of those, only a few will achieve that goal. I’m sure that many pros do build up their portfolio of images over time, but for most part, I believe they’re shooting for the present. I believe it’s probably not all that common that a landscape photographer gains acclaim for a picture that they’ve had for many years (unless it was great and they just never showed it before – or they became famous, and people became interested in their other work). In most other cases, photographers work on an assignment where they’ve got a deadline to produce a shot that will be used on a magazine cover or a billboard or some other place; they’ll be paid, and the picture will ultimately be forgotten. And in quite a few cases, like news, sports, or anything the paparazzi covers, the photographer will be trying to get their pictures to the newsroom within minutes – and the story will be completely forgotten within days.

I am oversimplifying, of course, and you do occasional get photos like Steve McCurry’s picture of an Afghan girl from the cover of National Geographic back in 1985, which is one of the most well known images anywhere:

The above image is served by National Geographic, copyright by NG/Steve McCurry, and links to an article providing background behind the photo. It also highlights how much photography isn’t about the technology, even though it’s vastly easier to improve our technology than to improve our pictures :).

With non-photographers, the situation is completely different. We are almost never shooting for the moment; we’re shooting to build a collection of memories to look back on at some point in the distant future. It’s rare to spend time flipping through pictures of a few weeks ago; it’s much more common to look back on photos from years ago. Your kids and their friends will probably look through that huge pile of baby pictures when they’re putting together some slideshow for their wedding in 2 or 3 decades from now – or once they have kids of their own. Often, we look back at all the pictures we have of loved ones after they’ve passed on. I’ll never have the skills it takes to capture a stranger the way the picture above does, but the picture of Olivia below is nonetheless timeless for me (despite the hand above her head, the lack of catch-light in the eyes, the over-exposed top of the hood, and various other flaws in the picture).

This particular pair of images also highlights how a photographer would try to avoid the branding displayed on the clothes (which Olivia currently refers to as the “arms one”, as she has a couple of other pink capes/towels with no arms). For me, it reminds me that this outfit was a gift from our friends in Japan, who shipped it to us as a gift upon news of Olivia being born. To me, that’s an important thing to remember.

Today vs. Tomorrow has several huge implications for non-photographers, though, that I think we as a group don’t pay nearly enough attention to:

- If you don’t organize your photos, you’ll have so many that you can’t find them (as mentioned above);

- If you don’t backup your photos, it’s unlikely that you’ll make it through 30 years without some kind of failure/accident wiping them out. Or they’ll be on a “CD” or something they used to call a “USB stick” or something that we’ll think of the same way we do of vacuum tube computers today, and you’ll be hoping the museum has has something capable of reading them.

- What’s good enough quality for sharing on Facebook today is going to look terrible compared to a phone built in to your watch in 30 years from now.

Speed and Low-Light

Sports photographers need speed. Event and wedding photographers need good low-light performance, at least whenever they’re not using flash. Landscape photographers often don’t need either, they need good dynamic range, a great tripod, and most importantly the right conditions. But non-photographers typically need both.

That’s because non-photographers are usually shooting people, those “people” are often kids, and those kids are generally not sitting and posing in front of a lighting setup – they’re trying to break their own indoor land-speed records. Even as they grow up, you’ll probably want to catch them at sports events – except they’re more likely to be playing in a dingy high school gym as opposed to a better-lit arena (unless your kids are super talented). Or worse, they’re in theater – or dance – and your light levels drop another few stops (even though they’re still moving).

What I said above about needing image quality for the future notwithstanding, the saving grace is that we don’t need pro-quality shots to remember the milestones and daily moments in our lives, so the compromises that come with a little less sharpness, or a little more noise, are generally quite bearable. Current-generation consumer DSLRs, for the most part, give us what we need to capture almost all the moments that we want with a decent level of quality. But another couple of stops won’t hurt :).

Still, I’m glad that I temporarily had the full-frame D700 around when Leo decided to play in near darkness on the bed (shot with the 50mm/1.4D @ ISO 3200, f/1.8, 1/30th):

Too Much Gear!

The one thing it seems photographers and non-photographers have in common is a gear obsession, even though we all actually know that great photographs aren’t about having great equipment. You need the right tools for the job, of course, but just as a professional race car driver with a Ford Focus (randomly selected car name, no offense to Focus drivers!) could beat me in a Ferrari (which I’d probably stall), a great photographer with an iPhone will get better shots than me with a D3x.

Still, I think part of the obsession with gear is that it’s the easiest thing to control – open your wallet, buy better stuff, and you usually can see the difference immediately. It doesn’t make your photos any better composed, but a D3s looks a lot better at ISO 6400 than a D40, and technology like VR or good high ISO goes a long way in hiding poor support techiques. If you could lose weight as easily as buying new camera gear, we’d all be lighter – and poorer. Improving our skills – like a healthy diet and consistent exercise – takes a lot more effort, and we’re lazy.

The most important non-difference

I do want to close by mentioning something that many will assume is a difference between the photographer and non-photographer, but that isn’t in my definition – at least not automatically. And that’s the desire to take good pictures. Yes, there are lots of non-photographers who don’t take the quality of their images too seriously, whereas most photographers inherently or else they wouldn’t be photographers. I say non-photographer to express that we have different end goals and different constraints – which in turn drive differences on the many dimensions listed above, which in turn mean that the advice that’s out there for an aspiring professional may not always be the right advice for us.

I’m certainly still trying to improve, but that doesn’t mean I’m trying to be a better photographer any more than trying to make healthier food for the kids would make me an aspiring chef. I’m just trying to be a better non-photographer.